Equipment

Equipment  Equipment

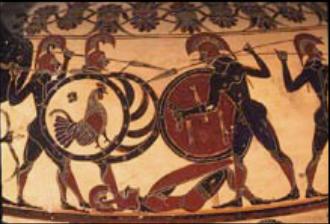

Equipment Estimates of a hoplite’s panoply in the early to middle 5th century BC (his shield, helmet, breastplate, sword, spear, and greaves) weighed from fifty to seventy pounds.

A hoplite’s shield weighing 13 pounds or more was an integral part of this equipment, as the century wore on the greaves and breastplate would be abandoned in favour of lighter equipment for mobility's' sake but the hoplon would remain as the most vital piece of the panoply well into the 4th century BC. Obviously used for protection against spear and sword thrusts, it also had a bowl shaped curve for one’s shoulder. When the opposing phalanxes met, hoplites in the rear used their shields to push the men in front of them forward. During battle, the shield was carried in the left hand and the spear in the right. This necessitated trust among neighbouring hoplites; each relied on the man to his right to protect his own vulnerable right side. The natural tendency of the phalanx therefore was to edge towards the right often causing an overlap and with the practice during this period that the best troops would be stationed on the right of the line it was usual that battles developed into clashes between the victorious wings of both armies.

The solid bronze, Corinthian style helmet that the average hoplite in the 5th century BC wore weighed about five pounds and covered the head and parts of the face and neck. The solid metal headpieces also provided no ventilation, often leading to dehydration. The burdensome covering allowed little range of vision and muffled much of the sounds around a man, including any orders from a commander. The isolation in wearing the helmet led to a battle experience largely based on the perception of pressure each man felt from those around him. In the second half of the 5th century this was replaced by more open style helmet, the pilos in Spartan and allied armies and the Boeotian helmet in Thebes.

The hoplite found body protection in his breastplate, a solid bronze, bell-shaped corset weighing thirty to forty pounds. As with the helmet, ventilation was nonexistent, leading to immediate discomfort and a drenching of sweat. Greaves, thin bronze sheets, were employed to protect the lower legs. Again in a search for mobility the bronze cuirass was often replaced by lighter material and the greaves were discarded.

The weapon of choice in these battles in the 5th century B.C was a eight foot long spear. The wooden shaft was made of ash or cornel wood, the head of iron, and the butt pike of bronze. Upon the collision with the enemy, the spear would often times break, thus the necessity of having a butt end available. However, this arrangement also endangered those hoplites in the rear ranks, for misdirection or accidental backward thrusts of the spear often led to the injury or death of one’s fellow soldier. In the case that the spear was lost or too damaged to use, a short sword was used. This was employed during the hand to hand combat experienced after the initial collision of forces.

For a visual comparison of hoplite equipment from the 5th to 4th centuries BC see here

The time leading up to battle was a test of nerve. The commanders made their final preparations after breakfast (mid-morning) and decided on the watchword, although not heavy drinkers the Greeks would tend to take a little 'Dutch courage' to steady the nerves. After breakfast the hoplite army marched out of camp and drew up in line of battle where they glared at each other for several minutes or even hours. Once formed into line the soldiers rested their shields against their knees and put their spears upright in the ground. The watchword was now made known to the troops, the watchword was in two parts, the challenge and the reply. This was necessary as at this time as there was little or no standardization in uniform or symbols to distinguish friend from foe when a melee was in progress. The symbol depicted on shields was up to the individuals choice. (see hoplon)

This was the time when courage was tested with the knowledge of what was to come. The test did not go without physical effects; involuntary defecation and urination, nausea, and light-headedness were not uncommon. Plutarch, recounts that Aratus, an Achaean general who lived in the third century BC, was prone to such symptoms. His enemies laughed at, “how the general of the Achaeans always had cramps in the bowels when a battle was imminent, and how torpor and dizziness would seize him as soon as the trumpeter stood by to give the signal” (Plutarch, Aratus 29.5)

In effect, the standoff was a test of morale amongst the ranks.

Once battle began, every hoplite had to stand his

ground, for one gap could be exploited and lead to defeat. If one man

cowered, the rest suffered. In this light, the success of the Spartan army

is not surprising. The Spartan soldier unlike his counterparts elsewhere

was a professional in an age of amateurs, he had no fields to tend or pots to

make. He was a soldier and spent most of his time in training for war. When

during the Theban campaigns of Agesilaus his allies complained that Sparta had

brought few soldiers compared to them, Agesilaus bid the army to stand up, then

asked all the potters then all the farmers, carpenters etc to sit, the only ones

left standing were the Spartans. While other city-states wore various styles of

panoplies and did not drill together, the Spartan army was a uniform mass

of scarlet cloaks (the distinctive Spartan shield and scarlet

cloak is seen at the right) . Their unit cohesion stemmed from their lengthy military

training and reflected the discipline so crucial to phalanx warfare. Plutarch's

description of the advancing Lacedaemonians in the Life of Lycurgus, a

ninth century BC Spartan lawgiver who transformed

the city-state into the dominant military power of ancient Greece,

gives a sense of what an opposing hoplite felt as he stared the intimidating

army.

“… It was a sight equally and terrifying when they marched in step

with the rhythm of the flute, without any gap in their line of battle,

and with no confusion in their souls, but calmly and cheerfully moving

with the strains of their hymn to their deadly fight.”

The march toward the enemy and the initial collision of forces was a balance between momentum and cohesion. The phalanx had to meet its enemy with enough momentum to move forward, but it also had to maintain order within the ranks so not to allow gaps between columns. The importance of unity and cohesion among troops cannot be overemphasized. Few Greek armies were cable of advancing in line over any great distance without becoming disordered For this reason, the more experienced troops were placed in the rear lines of the phalanx to have the strength and bearing to maintain a constant push forward once past the initial collision. As the opposing armies marched, breathing became difficult; hearing was virtually impossible except for the sound of war cries and marching feet. Thousands of feet under the weight of panalopies kicked up dust from the dry summer’s ground.

Keeping ones nerve was everything.

The War Songs of Tyrtaeus, poem written about the Second Messenian War, defines the connection

between courage and lack thereof on the battlefield and its influence on victory

and defeat.

“Now of those, who dare, abiding one beside another, to advance to the

close fray, and the foremost champions, fewer die, and they save the people

in the rear; but in men that fear, all excellence is lost. No one could

ever in

words go through those several ills, which befall a man, if he has been actuated

by cowardice. For ‘tis grievous to wound in the rear the back of a

flying man

in hostile war. Shameful too is a corpse lying low in the dust, wounded

behind

in the back by the point of a spear.”

It was those who faltered that contributed to the death of their countrymen. Thus, in the advance, order among men could decide victory and defeat. Speed and fear had to be balanced with the desire to strike the enemy with momentum. If the phalanx went too fast it would become disordered and eventually fall before an enemy's more tightly bound phalanx. On the level of the individual hoplite, fear had to be controlled so not to break the chain of interdependence among troops.

At 3 or 4 stadia distance if neither side had broken by this time both sides would now start to sing the 'paean' , hymn summoning the aid of the god of battle. The two armies would march slowly toward each other and at a stadions distance apart a sacrifice to the gods would be made, the two forces would start a final run prepared for perhaps the most brutal collision of forces. Often one or other of the lines would fail to come to grips and would break and run. At the 'Tearless battle' in 368 the charge of the Lacedaemonians was so terrifying that few of the Arcadians or Argives waited to come within spear thrust range.

Timing was vital, too soon and the hoplites would be exhausted by the run, too late and they would fail to gain momentum. At about 600 feet, a stadion, apart a trumpet would sound the charge , the line breaking into a run and emitting war cries. In the final stages of the charge the hoplite would have adjusted his weapons, the shield normally carried sideways on the left would have been moved to cover his whole body. The hoplites on the front line presumably advanced with their spears carried underhand, aiming for the enemy’s groin and legs.

After the initial surge forward came to a standstill, the front three lines would stab their enemy holding the spear overhand, as illustrated on the Chigi vase. At this point, the primary targets were the neck, shoulders, and face. However, if the spear broke ,a short sword was used. Meanwhile, the back five lines pushed forward with their shields. Action following the collision was focused on pushing through breaches in the line created by those hoplite’s engaged in bloody hand to hand combat at the front.

As a defeated phalanx collapsed, there were two options:

flee or retreat in an organized fashion. The latter option was rare but

offered a greater chance of survival. However, once it was clear that

victory was not one’s side, a mob flight usually ensued. Under the

circumstances of phalanx warfare, if one man left it was observed that others

would follow or risk being severely weakened if attempting to lead an organized

retreat. Once mob flight took over, casualties soared.

“The Lacedaemonians were at no less for men to kill; for the gods gave them

such

occupation as they would not have even sought by prayer; for how can it be

thought

otherwise than an appointment of the gods, that a multitude of enemies thus

terror-stricken, astounded, exposing their unarmed sides, no one turning to

resist, but

all contributing in every way to their own destruction …” (Xenophon)

To escape more easily and quickly fleeing soldiers would throw away their equipment, particularly their shields. These 'shield flingers' were punished with a heavy fine in Athens but it was difficult to enforce since the difference between deliberately throwing it away and losing it in battle was blurred. In Sparta losing ones shield was the crime of a coward and offenders could be beaten by any citizen at any time. The reason being that a shield is for the protection of the whole line while a helmet or cuirass was for personal protection.

Total annihilation was uncommon in Greek warfare due to limited effectiveness of cavalry forces. The infantry were not suited to chasing down fleeing enemies due to the weight of their equipment and the loss of cohesion that could ensue and make them vulnerable to counter attack. At this time in history, not all Greek city-states had cavalry forces and if they did they were small, and not well trained, therefore the vulnerability of the fleeing enemies was not exploited Thus, casualty rates amongst hoplites seem relatively low. In a battle a losing phalanx might lose fifteen per cent of its strength, either through outright killing, death from wounds or in the massacre which followed flight.

After the pursuit was over and the vanquished had acknowledged defeat by asking for a truce. The bodies of the enemy were stripped of armour, clothing and valuables and was normally put into a common pool. A proportion was dedicated to the gods and the rest sold or auctioned. A trophy was erected usually at the point were the enemy had begun to flee. The defeated after sending a herald asking for a truce were usually allowed to bury their dead. The dead of both sides were usually buried quickly in the hot greek climate and to stop scavengers eating the bodies. After the battle of Delium in 424 BC the Boeotians only granted permission to the Athenians after 17 days thus making identification very difficult.

|

Why did men willingly go through such an ordeal considering

the harsh experiences of the hoplite in a battle and the interdependence of each man

upon another inherent in phalanx battle. In

nearly all city-states men were deployed in their phalanxes by tribe or in the

case of Spartans in their enomotia or sworn band, and most

likely of course were well acquainted with those of their own town or deme. In battle each man relied

upon another; having a neighbour or relative nearby him radically alters the

situation a man is in. Amongst strangers, a man is less prone to hide cowardice. However, the peer pressure brought about by placing a man among friends and

family members raises a man’s pride. Fear of failure drives him.

The sense that he faces danger with those he cares for gives him purpose. Of

course this is only a generalisation and it is the fear of being seen to be a

coward which is the motivation. There will always be those who claim to have

left a vital piece of equipment in their tent and must go back for it or who

help a wounded man back to camp and remain to care for him. Xenophon,

a Greek soldier and historian, remarked, “it has been seen, that a troop never

be stronger than when it is formed of fellow-combatants that are friends,”.

(Xenophon, Cyropaedia

7.1.30) One

fought not only to protect an abstract notions such as freedom or liberty, but

also to protect his friends and family. Thus, running away or breaking

ranks meant desertion of those who he had grown up with except when we are all

running away.

The crucial cohesion that decides battles was then dependent upon trust and

pressure. While phalanx warfare tested a man’s nerve, he held his ground

in fear of failure in the eyes of those he respected. He was also ashamed to

leave those he cared for unprotected.